I’ve been training in the martial art called Aikido for more than two decades. I hold the rank of Shodan (1st degree black belt), and I’m training/studying for my next rank (Nidan, or 2nd degree).

People unfamiliar with Aikido, but who may have heard something about it, often tell me that they have heard Aikido is about “using the opponent’s energy against them.”

At the most shallow, mundane level, there is some truth to this. But it misses the point.

I think that all martial arts deal in the same fundamental precepts at some level. But different arts, and different teachers in those arts, and different techniques in those arts, all live on a number of different spectrums — hard vs soft, linear vs circular, direct vs indirect, static vs moving, subtle vs crude, instructional vs practical, even effective vs ineffective.

In general, Aikido is usually on the “softer” side of the spectrum of all martial arts — even though there’s a wide spectrum within the art itself. It’s more subtle, often (but not always) more circular, and (I think) tends to require movement to work. I won’t get into how practical it is, because that depends heavily on what you’re trying to accomplish, and it becomes an almost religious discussion.

Which, ironically, brings me to what I wanted to talk about.

These days, in politics and social media (can they even be separated?), it has become more and more expected that we “take sides” on almost all issues. Take a position. Defend it. Dig in.

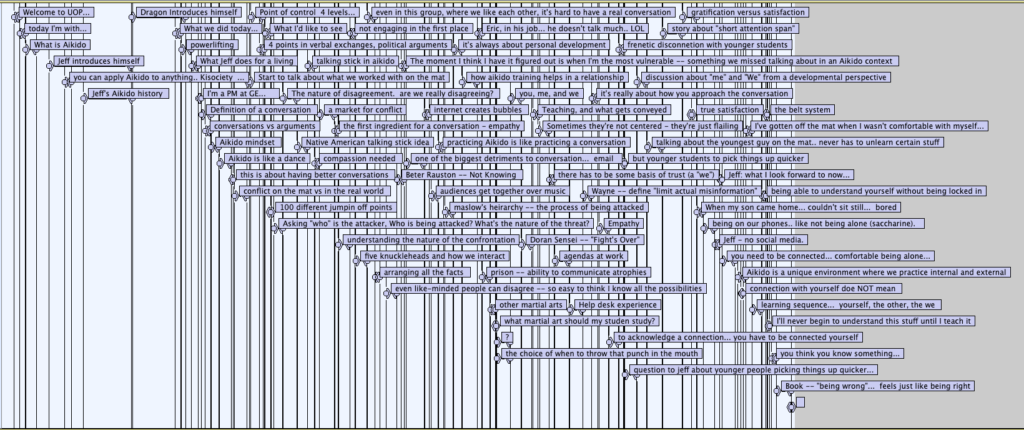

I think we study this idea in Aikido, even we’re not always aware that we’re studying it. I find this particularly apparent when I’m in the role of “Sempai” (more senior student), and even more particularly when I’m in the role of “Uke” (the attacker). In Aikido, we’re almost always doing paired practice. We take turns being the “attacker” (Uke), and the “defender” (Nage, or Tori). In these roles, it usually ends with Nage executing some technique on Uke. Uke is usually the one who falls.

Often, as Sempai, I find myself reminding my partner to “relax” in some way. Maybe I’ll gently shake their shoulder or forearm to show how much tension they’re holding. Or I’ll playfully remind them that it’s OK to move their feet. Or to breathe. You’d be surprised how often we forget to breathe.

Let me be clear — I’m still learning these things, too. Perhaps at a different level, but there’s never an end to the learning. But, as we get more familiar with Aikido, we learn that continuing to be able to move is a sign that we’re getting better. Ideally, we remain more centered and balanced regardless of the attack; always able to move. After all, it’s really not possible to move effectively without being centered and balanced.

“Taking a position” is a dangerous proposition.

If I “take a position” in Aikido, it implies I need to defend that position.

Defending a position can look like me trying not to move my feet. It can look like me taking a punch, or simply resisting a movement with my arms. It can even manifest as a dogged determination to execute a particular technique because that’s what we’re trying to practice, even when it’s clear that the situation calls for something different in the moment.

If this sounds a little to wishy-washy for you, I might remind you that whatever attack you’re dealing with at the moment isn’t the end of the situation. Aikido, after all, comes from a tradition of “multiple attackers, weapons everywhere.” To me, this mindset has never been more apropos than today, in our world of 24-hour late-breaking “news” (/opinion) and social media rants.

So. In Aikido, we’re constantly training ourselves to be physically and mentally (even, dare I say, spiritually) able to remain centered and balanced, but to avoid “taking a position.” I think this is a lesson that more of us could use in everyday life these days.

Many of us would agree that the world feels “out of balance” in some respects. As my Taiji teacher says: “When something is out of balance, the answer is never more tension.”