Leave it to John Cleese to sum it all up.

Sometimes I think comedians would clearly make the best politicians. Comedy shines a light on our own absurdity.

Leave it to John Cleese to sum it all up.

Sometimes I think comedians would clearly make the best politicians. Comedy shines a light on our own absurdity.

A recent flurry of activity on X got my attention (thank you, Jeff). From a response to a post about President Trump’s recent “bloodbath” statement…

This is a pervasive sentiment — and it’s a sentiment that works in both directions.

Truth: The Left ignored the economic statement that Trump was making (involving a tariff on China)

Truth: Using the word “bloodbath” in today’s world is, at best, careless (at worst, irresponsible).

Surely: Trump never intended to encourage real, literal violence.

Surely: The Left doesn’t like the China tariff on Chinese cars — simply didn’t want to listen, even if the statement has merit.

Surely: Trump is no dummy. He instinctively knew the word “bloodbath” would get attention. He is a master manipulator of the media, despite his complaints about it.

Surely: The Left seized the opportunity to fan flames and distract.

Truth: Who wins? The media.

I believe that there is almost always truth at the heart of both left and right — even amongst the lies. To get at a more holistic truth requires that we see truth in the other guy’s statements as well as ours, and see the lies in our own as well as the other guy’s.

I was at the gym this morning, where I overheard a guy make a comment to someone else: “He committed treason! I’m not a Democrat; I served my country.”

I don’t know who they were talking about. But the “I’m not a Democrat; I served my country” part stuck in my craw during my workout.

Clearly, this guy assumed that Democrats don’t serve in the military.

I suppose I could have confronted the guy (a very big, intimidating guy, I might add) about it. Perhaps I could have been charming enough to actually do that well. Perhaps I could have learned something. Perhaps we both could have learned something.

Or perhaps I just chickened out.

I actually think it was not an appropriate place to engage in a political conversation. That’s certainly not what I was there for.

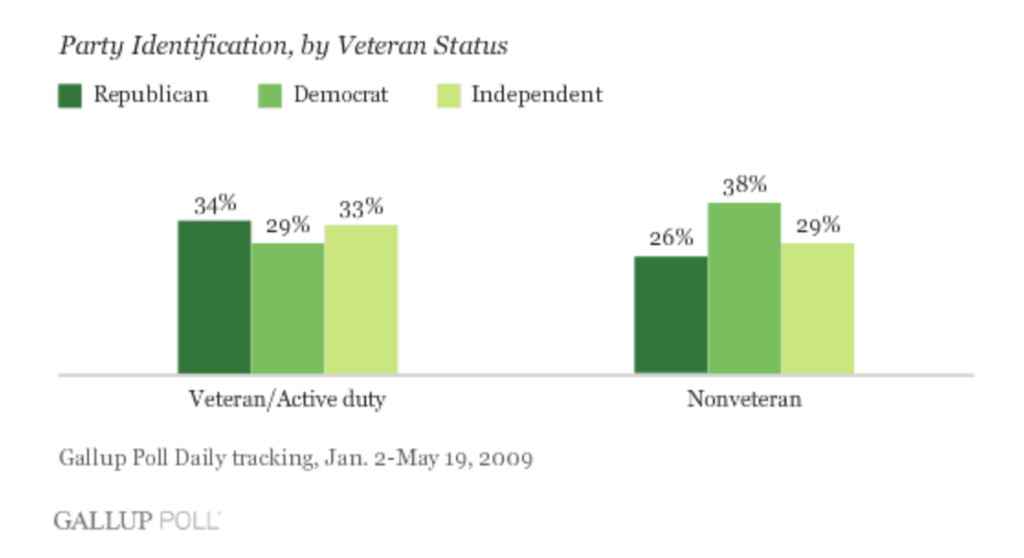

Anyway… I looked up the statistics on military service and political party. From news.gallup.com, the upshot is this:

So, yes, veterans tend to be Republicans more than Democrats. But not by as much as the guy at the gym probably thought. Certainly it wasn’t nearly as clear-cut if you include independents (I’m assuming the guy was Republican).

Which brings me to the real point of this post.

Very often, in any kind of a heated debate or argument, I hear people say things like:

“How could they think X if they do Y?”

“How can they think that could work?”

“What are they thinking?”

Often, my response is: “That’s not a bad question to be asking.”

But, in reality, they’re not usually posed as actual questions. They’re statements, disguised as questions. What they really meant by the above ‘questions’ was:

“They don’t really think X, or they wouldn’t do Y.”

“That won’t work, and they’re stupid if they think it will.”

“They’re not thinking.”

But if we rephrased the ‘questions’ slightly, in such a way that they assume validity from the get-go, they might sound like this:

“How is it that some intelligent people think X if they do Y?”

“How is it that reasonable people can think that could work?”

“I wonder how they came to this conclusion?”

…and all of these could be followed up with an implicit “What am I missing?”

If the “questions” are actual questions — that assume validity — then there’s value in them. Otherwise, they’re just statements in the form of questions, meant to invalidate something someone else did or said. This never gets anywhere.

When my wife sent me this article from Neuroscience News, I immediately loved the title.

Humility is a rare commodity these days — or at least open, public humility. So much of the so-called “conversation” we hear and read these days is 90% posturin, denial, and deflection as opposed to listening and learning. Vulnerability is suicide in today’s sound-byte culture in which we look for the worst in others so that we can amplify it, while at the same time shrug off the worst in ourselves as anomaly.

You should have a high bar for what evidence you require to change your mind.

When I read this in the article, I bristled a little. I immediately recalled something I heard or read once that showed that, while naturally have a high bar for changing our mind, we actually have a rather ridiculously low threshold for forming those opinions in the first place.

Believing this is probably why I have become inherently averse to forming strong opinions, at least for long. I’m a consummate “fence-sitter,” looking to both sides for as long as possible before having to come down and make a decision on something, and then remaining willing to jump back up there frequently.

I get a lot of flack about my fence-sitting from people who know me. I joke that “you can see so much better from up here.”

Great article. Worth a read.

I’ve been thinking a lot about a particular email thread. Perhaps I’ve mentioned that, for at least a decade, I’ve been corresponding with a group I call the “Five Knuckleheads” (I wasn’t the one that coined the term). Long time friends, and my brother. Two staunch conservatives, my brother and myself somewhere in the middle — he probably more conservative than I – and, well, I think we might have actually permanently lost our staunch liberal. I miss him, because it make me the “liberal representative” of the group.

I don’t consider myself liberal. I consider myself staunchly and relentlessly centrist. I have lots of liberal friends who consider me rather conservative. But, since I have no conservative friends that consider me conservative, I guess I’m probably liberal.

Recently the issue of affirmative action came up in our group, with the most vocal conservative making the statement (and I’m paraphrasing): “Democrats (that is, liberals) advocate for differing standards of academic acceptance and excellence for black than for whites. Therefore they must believe blacks are inferior to whites.”

I challenged him to introduce me to a single liberal who would say “yes, that’s what I think.” Just one. I went on to say that, if he could not, then he has no basis for an argument supporting this idea of liberal racism, because he can’t find anyone who agrees with what he’s claiming to disagree with.

This led to several other spinoff thoughts, which is what I’ve been giving a lot of thought.

Then I realized that I was finding myself in the position of defending affirmative action on behalf of all liberals.

Here’s the thing. Well, two things.

First, I’m not in favor of affirmative action. I’m rather conservative on this issue. I’m angry with myself for being maneuvered into a position where I feel I need to defend it.

Second — and most importantly — arguing ANY individual issue is not really my mission. My mission is understanding; understanding other people’s points of view, and helping others do the same. I started chiming in on this thread originally to try and help my conservative friend consider that if there isn’t a single liberal on earth that actually believes blacks are inferior to whites, and yet liberals in general are in favor of affirmative action, then maybe, just maybe, there might be something else going on here.

I failed gain. People tend to just double down on their original arguments when I try to get them to look for a different solution. Perhaps they don’t even want to admit that there’s a misunderstanding at all — at least not on their part. Not understanding is uncomfortable. it feels yucky. We are driven to eradicate it — even if we’re wrong.

So. Affirmative action.

Let’s start with the statement that affirmative action is a form of reverse racism, because it gives preferential treatment based on race. Liberals might disagree. The might say it finally levels the playing field, after many years of racist practices and even policies, resulting in a much steeper climb for minorities to get into top colleges (for instance) than for whites.

Maybe. But I think a reasonable argument can be made that affirmative action results in accepting minority candidates, in some cases, that are less academically qualified than their non-minority counterparts, in favor of helping meet admission standards for diversity.

IF that’s true, then it’s easy to see how conservatives call this reverse racism, and that, either liberals don’t agree (but can’t explain why), or they reluctantly agree, but they approve of it — in light of other circumstances.

That is, it can be argued that liberals — as a class (perhaps not individually) — would agree that a “certain degree” of reverse racism is preferable to a lack of diversity in colleges.

This, then, comes back to a recurring theme for me — a belief that conservatives and liberals tend to have the same values. Just in different priorities. Sometimes very slightly different. All reasonable people value equal standards. All reasonable people value diversity. However, which is more important, and at what cost? That’s the rub, and worth understanding.

I’ve thought of many of the topics in this video for a decade or so. Some of us who are old enough to have seen the rise of modern communication: 24-hour news, the internet, mobile phones, common-man videos, and of course social media. We have some sense that these things, which held so much promise at first, seem now to have gotten dark and twisted and done the opposite of what the promise was.

Some points from the video (from Veritasium):

People have debated for centuries what is important in life. Somewhere in the discussion, the idea of “values” usually comes up. Values can be thought of as defining your character. Some think it’s the other way around. But when it comes to any thinking about what make s a good live, values matter. So, it seems to me, there’s no doubt that thinking and meditating and praying and talking about what we value as human beings; individually, in groups, as a species; is, well, valuable.

However, I think that perhaps this path is fraught with peril.

When we talk about what we value, or what others value, it seems that the discussion very quickly becomes one of a binary nature. We value this over that. You don’t value that, but I do, etc.

When I have real conversations with people (as opposed to arguments or rants), I usually find out, when we go deep enough, that we all value similar things. Similar — not the same. In general. I mean, who among us would say out loud against such values as integrity, honesty, loyalty, strength, creativity… you get the idea.

In a recent conversation with Claude AI (claude.ai), we went round and round on how liberals and conservatives see the world, and Claude ended up saying this:

Certainly – while liberals and conservatives often come to very different conclusions about key ethical issues, there are certain fundamental moral principles held in common across ideological lines:

While stark divides exist on major sociopolitical issues, these examples illustrate shared commitments to core humanistic values of compassion, fairness, rights, community and lawful order that cross ideological divisions. Reasonable people of conscience want ethical outcomes – debates are often over competing ethical applications. Identifying consensus principles can aid cooperation.

It isn’t my intention to compare liberals and conservatives here — God forbid. My intention is to dig into why we so often get all wrapped around the axle is when we compare values with each other — and of course “liberal values” or “conservative values” is a natural destination on that path. Don’t get me started on the idea of “family values” — I mean, who really owns those?

My intention here is to point out so often the source of our conflicts with each other is rooted in how we try to define what our values are for ourselves, and what we assume “must” be the values of our “opponents.“

Let’s take an example: “fairness.” Different people define “fairness” differently. In fact, the same people define fairness differently at different times and in different circumstances. Fairness often gets confused with justice. Whether or not fairness is even to be expected is debatable. Fairness is a rather squishy concept.

Is it “fair,“ for instance, to treat everyone the same, or is it more fair to treat everyone how they themselves wish to be treated? Or perhaps the golden rule applies, and fairness means that we should treat everyone the way we ourselves wish to be treated.

Is it fair for someone who makes $50,000 a year to pay 40% of it in taxes, while a billionaire pays less than 10%? Is it fair that the same billionaire’s 10% is considerably more than the other persons 40%? Which is fair? Who does more for society? Is that even a factor in discussing fairness?

We all have answers. Arguments to make. Opinions.

My point is that we all generally value “fairness.” But we probably mean different things.

Furthermore, even if we did agree on a general definition of individual values, I think we still get wrapped around the axel when we try to apply those values in context, because our values conflict — yes, with each other, but I’m talking about within ourselves. I might value spontaneity, but being spontaneous can be expensive and I also value frugality. I might value loyalty, but I also value integrity and that means I might have to stop supporting someone who demonstrates unethical behavior. I might value strength and the ability to persevere, but I also value flexibility and the ability to redefine myself.

Life seems less about the values than it does about how we prioritize them.

And PRIORITY is a whole ‘nother subject.

I’m a professional project manager. My work life is all about clarifying, detecting, communicating, managing, and enforcing priorities. At the highest level, my company values are written into our training as: Safety, Quality, Delivery, Cost — in that order. And yet, there are many times when we make decisions that put cost ahead of other factors on smaller levels. When we start talking about prioritization, we bring in a whole set factors that determine our priorities.

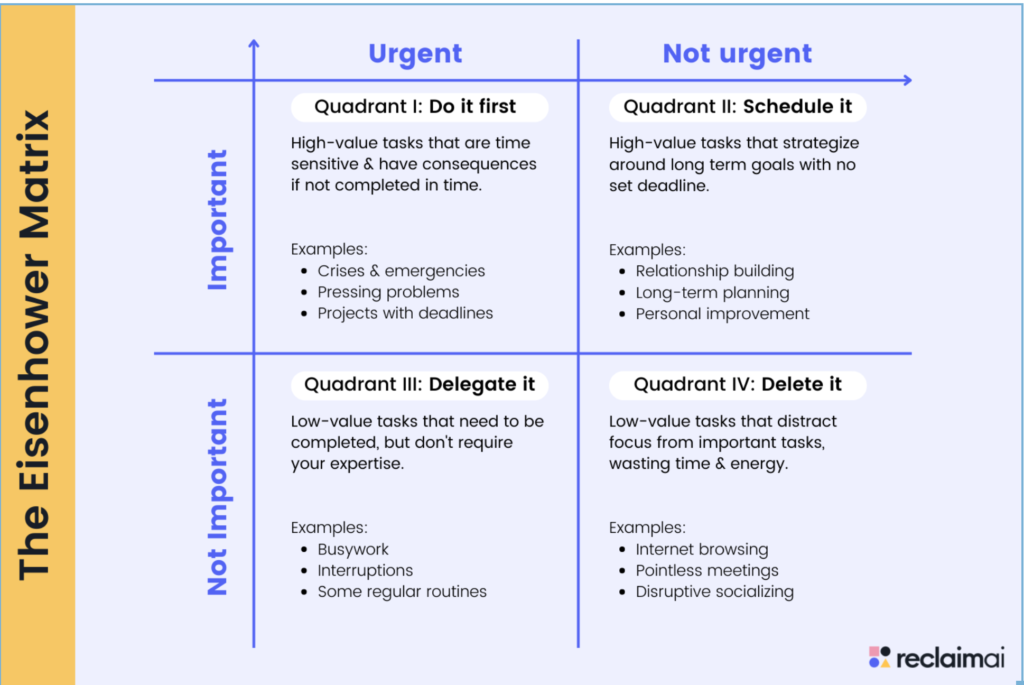

Most of us have seen a grid that looks something like this:

Notice that the word “value” appears repeatedly. Notice that, ideally, you want to spend most of your time in the upper-right quadrant, and we all feel like we spend too much time in two “urgent” quadrants.

Importance and Urgency can, themselves, be broken down into factors that ebb and flow with situation, time, personalities, etc. For instance, when you’re trying to manifest something in the real world, the concept of “opportunity” often plays a factor in the “urgency” space.

We see this quite often in politics. One need look no further than to notice that every time there’s a school shooting, the issue of gun laws becomes more urgent, because there’s an opportunity, politically, to possibly make a difference. I think most of us would agree that the federal deficit and debt, are important. They don’t ever seem to be urgent, however. Consider climate change. Even the most staunch deniers probably agree that this is an important issue. But whether it’s urgent or not depends on how much you trust science, or which studies you believe, or who’s communicating them, or how close you live to the ocean. What’s more important/urgent to a politician in a re-election campaign — climate change that hasn’t yet directly affected her constituency, or the economy, which always does?

We all value a clean, healthy planet. We all value a healthy economy. We all value fiscal health on every level. We all value safety for our children. We all value equal opportunity. We all value life.

Yet we so often act as if those we argue with do not.

The time you’re having an argument — especially a heated one — I urge you to think about values, but especially think about values in terms of their priority. Think about your priorities, and those of the person you’re connecting with, in terms of the very specific contacts you are in. Think of this single conversation; your relationship with this person; the mood you and they are in — then maybe think about the broader implications of your conversation to your community, your country, and the world.

It’s not that the other person doesn’t value what you do.

It’s that they value other things, too.

And so do you.

To see this is to see a path forward.

I’ve been training in the martial art called Aikido for more than two decades. I hold the rank of Shodan (1st degree black belt), and I’m training/studying for my next rank (Nidan, or 2nd degree).

People unfamiliar with Aikido, but who may have heard something about it, often tell me that they have heard Aikido is about “using the opponent’s energy against them.”

At the most shallow, mundane level, there is some truth to this. But it misses the point.

I think that all martial arts deal in the same fundamental precepts at some level. But different arts, and different teachers in those arts, and different techniques in those arts, all live on a number of different spectrums — hard vs soft, linear vs circular, direct vs indirect, static vs moving, subtle vs crude, instructional vs practical, even effective vs ineffective.

In general, Aikido is usually on the “softer” side of the spectrum of all martial arts — even though there’s a wide spectrum within the art itself. It’s more subtle, often (but not always) more circular, and (I think) tends to require movement to work. I won’t get into how practical it is, because that depends heavily on what you’re trying to accomplish, and it becomes an almost religious discussion.

Which, ironically, brings me to what I wanted to talk about.

These days, in politics and social media (can they even be separated?), it has become more and more expected that we “take sides” on almost all issues. Take a position. Defend it. Dig in.

I think we study this idea in Aikido, even we’re not always aware that we’re studying it. I find this particularly apparent when I’m in the role of “Sempai” (more senior student), and even more particularly when I’m in the role of “Uke” (the attacker). In Aikido, we’re almost always doing paired practice. We take turns being the “attacker” (Uke), and the “defender” (Nage, or Tori). In these roles, it usually ends with Nage executing some technique on Uke. Uke is usually the one who falls.

Often, as Sempai, I find myself reminding my partner to “relax” in some way. Maybe I’ll gently shake their shoulder or forearm to show how much tension they’re holding. Or I’ll playfully remind them that it’s OK to move their feet. Or to breathe. You’d be surprised how often we forget to breathe.

Let me be clear — I’m still learning these things, too. Perhaps at a different level, but there’s never an end to the learning. But, as we get more familiar with Aikido, we learn that continuing to be able to move is a sign that we’re getting better. Ideally, we remain more centered and balanced regardless of the attack; always able to move. After all, it’s really not possible to move effectively without being centered and balanced.

“Taking a position” is a dangerous proposition.

If I “take a position” in Aikido, it implies I need to defend that position.

Defending a position can look like me trying not to move my feet. It can look like me taking a punch, or simply resisting a movement with my arms. It can even manifest as a dogged determination to execute a particular technique because that’s what we’re trying to practice, even when it’s clear that the situation calls for something different in the moment.

If this sounds a little to wishy-washy for you, I might remind you that whatever attack you’re dealing with at the moment isn’t the end of the situation. Aikido, after all, comes from a tradition of “multiple attackers, weapons everywhere.” To me, this mindset has never been more apropos than today, in our world of 24-hour late-breaking “news” (/opinion) and social media rants.

So. In Aikido, we’re constantly training ourselves to be physically and mentally (even, dare I say, spiritually) able to remain centered and balanced, but to avoid “taking a position.” I think this is a lesson that more of us could use in everyday life these days.

Many of us would agree that the world feels “out of balance” in some respects. As my Taiji teacher says: “When something is out of balance, the answer is never more tension.”

I mentioned to someone recently that my daughter is “on the spectrum,” which is shorthand for saying that she’s autistic to some degree. However, the phrase is horribly imprecise, and can lead to some serious misunderstandings.

Autism has a very wide range of symptoms — from people like my daughter who may be somewhat socially awkward, to people who are severely unable to communicate.

I tell people that you’d “never know” my daughter is “autistic” until maybe you’d gotten to know her a little. You’d notice that she’s quite verbal, but she uses words in interesting ways sometimes. She has a great sense of humor, but she doesn’t “get” jokes the same way other people do. She’s very literal, and so doesn’t always pick up on social queues that are, for most of us, obvious.

As a person “on the spectrum,” she’s in very elite company. Dan Akroyd, Elon Musk, and Anthony Hopkins come to mind, for instance.

Anyway, this post isn’t about Autism. It’s about the “spectrum.”

I believe that there is also a spectrum of “open-mindedness.” This isn’t fixed per person, or group. It moves with different issues, different circumstances, audiences.

Nobody likes to be called “closed-minded.” Or, never mind using a broad label like that — nobody even likes the suggestion: “…so, your mind is closed on this subject, correct?”

“What?! NO! My mind isn’t closed! I just know that I’m right about it.”

“So, is there anything I could say that might change your mind?”

“Probably not, no.”

“That sounds like a closed mind — on this subject.”

I think we each have a spectrum of closed- (or open-) mindedness, perhaps in general, and almost assuredly on individual topics. I think we become more close-minded when threatened. Or among people who we feel threatened by (even if they haven’t threatened us). Or in situations in which we feel like we might be threatened.

…and, by “threatened,” I don’t mean physically. I don’t mean being outright insulted. Although those apply, too.

The most pervasive and insidious situation we might find ourselves in, in which we might feel “threatened” is… (wait for it….) ANY TIME WE MIGHT HAVE TO CHANGE OUR MINDS.

You see the problem? We become more close-minded any time we might have to change our minds. And the more the topic matters, the more close-minded we are apt to get.

Is it any wonder that it’s so hard to have a conversation with someone about anything that matters?

So.

Notice when you feel “threatened,” in the sense that you’re being asked to change your mind.

Notice how this makes you put your guard — how, to some extend, on this topic under these circumstances, your mind is closed. Notice where you are on “the spectrum.” It’s OK — it’s how we’re ALL wired.

Try to get into the habit of changing your mind. Of feeling GOOD about changing your mind. Do that by practicing the art of expressing someone else’s point of view, to THEIR satisfaction.

Changing your mind is not a sign of weakness. It’s a sign that you’re learning.

The more we practice having our minds changed, the more chance we’ll have to return the favor.

I just created a YouTube Channel. Thought I’d start with this…