My family and I are spending a couple of days at Claytor Lake. We rented a “cabin” (sleeps 16 — long story) and I’m taking a day off work. My wife, daughter, and mother-in-law are joined by my son and his girlfriend, who are visiting us from college.

I thought to myself about a week ago that it might be interesting to blog every day on some experience of being wrong. This morning something happened that made me laugh and shake my head. It was mostly my mother-in-law’s experience, but I unwittingly instigated it.

I mentioned we’re at a cabin. This means we don’t have all our usual kitchen supplies, and some of the usual things are not in the usual containers.

So, Gramma was fixing her coffee, and she asked me where the sugar was. I told her it was in the Illy coffee container. I put it in there because Illy coffee comes in a handy steel container that travels well. She thanked me and went about her business.

After she finished her breakfast, she told me that the sugar she put in her coffee was actually raisins. It was at this point that I realized there were two Illy coffee containers — one of which did, in fact, contain raisins. Neither was labeled.

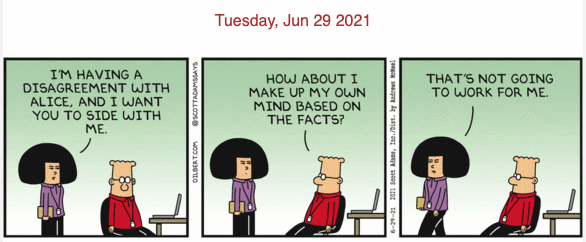

I asked her why, when she noticed that the “sugar” looked a lot like raisins, she didn’t take notice and re-evaluate. She told me she thought maybe the sugar was in the form of “little clumps of brown sugar.” I thanked her for her complete faith in me, and apologized for my error. But, in my own mind, I thought that perhaps, after 86 years, she could probably have trusted her own judgment enough to know the difference between sugar and raisins.

So, from my perspective, when I told her where the sugar was, I felt like I was right. When I realized her mistake, I realized mine. No biggie.

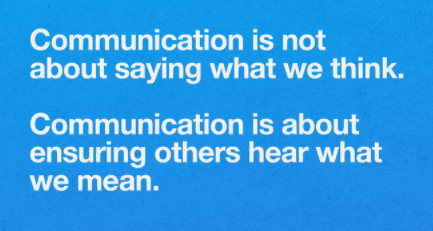

From her perspective, however, the experience is fascinating. She knew something was “wrong” with the sugar, but her answer to that problem was that the sugar came in a form that looked very different than the white, granulated kind — little clumps of brown. In her mind, it was easier to believe in a form of sugar that she had never before seen in all her life, than to consider that maybe I gave her bad info.

I find that fascinating.