I just read a great article, sent to me by my long-time friend, Wayne. Wayne is really smart. I really value what Wayne says. And yet Wayne and I disagree a lot. So much so that, over the years, I don’t even open most of his emails because the subject line seems so biased.

I’ve been focusing my energy these days on trying to change the way we have conversations (see understandingonpurpose.com), so sometimes I take a deep breath, crack my neck, and remind myself that Wayne’s thoughts can be a rich source of training material (ahem). I mean, if I can’t change the conversation with a long-time friend, what chance do I have with relative strangers?

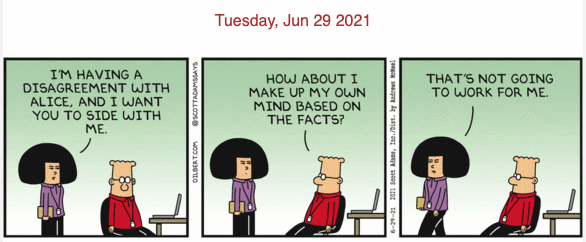

So. Wayne sent me this article, about the science behind “winning an argument.”

“Winning an argument,” in this context, could probably be defined as “bringing the other person to your point of view.” Long story there, but let’s leave it at that for now.

I’ve been training in a martial art called Aikido for at least 22 years. People outside Aikido circles sometimes interpret the movements of Aikido as “using your opponent’s energy against them.” This is actually quite far off the mark, but for now it’ll do, because it distinguishes this mind set from that of most arts that focus on kicks and punches, in which the (equally off the mark) objective is to “meet the opponent’s attack with greater speed and power, and deliver killing blows.” Want more? Check out another blog of mine, at mikeidomo.

The reason I train in Aikido is because if I took the way I see conflict (ideally) and put it into a dance, it would look like Aikido. Almost everything in the physical “dance” of Aikido is analogous to something in the verbal dance of a conversation — particularly debate, or argument.

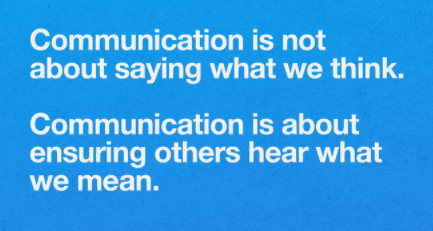

So. A line in this article struck me (so to speak):

I loved this, because I’ve often taught that our relationship to our attacker in Aikido is a “frame” — I usually use this language when working with dancers, because they immediately get it. But it goes even deeper. The scientific study referenced in the article drew a conclusion:

To those of us who study Aikido, this sounds a lot like “blending” with an attack (as opposed to blocking it).

Thanks, Wayne.